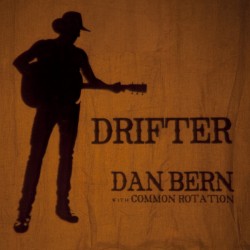

Drifter

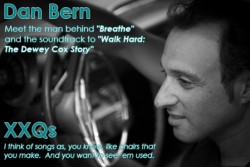

By James Campion

Prolific Songwriter’s Ode to Perpetual Motion

I first heard a selection of the songs that ended up on Dan Bern’s brilliant new record, Drifter in November of last year in the lobby of a refurbished theater in Beacon, New York and then the next day during a promotional live web cast for a magazine in downtown Manhattan. He played a few more at Joe’s Pub in Greenwich Village that night and in late-December at Mexicali’s Blues Café in Teaneck, New Jersey. Separated from the eventual collected work, which both musically and lyrically segues in and out of each song as if psychic travelogue — a yearning to discover, hide, escape and return to a home that is at once geographical and spiritual — it was as if Bern were symbolically ushering the songs through a rigorous performance trial, first solo and then with his new collaborators, the creatively versatile Common Rotation.

Later in the winter, as is his wont, Bern sent me a rough mix of the material he wanted to put on the eventual release. For weeks I played it in my office, in the car, and in the background during gatherings of the local tribes, but it wasn’t until late one night that it hit me; this is as close to a running commentary on the American folk ethic as could be laid down in one place — a literal ode to perpetual motion, Jay Gatsby’s ride through the valley of ashes to his unreachable green light at the end of the dock.

Drifter is a statement — Bern’s, a generation’s, a genre’s — the effects of traveling on the traveler for good or ill. It is survival. It is change. It is acceptance. Serpentine movement as philosophical, ethereal, political, nostalgic, narcotic, and introspective on tracks like “Luke the Drifter,” “Raining in Madrid,” and “Haarlem,” “Carried Away,” “Home,” and “Mexican Vacation,” “I’m Not From Around Here,” and “Love Makes The Other World Go Round,” which is the type of denouement that eases seamlessly into the epilogue of “These Living Dreams.” Many, if not all the songs deal with a transitory experience — aging, evolving, moving along through life observationally — it is also replete with an imagining of a better “place” through vivid dreams and visions of hope.

A concept record? Nah. Bern was quick to dismiss that on a late-night phone call in March, after I sent him a manically cobbled deconstruction of the record under the influence of my sudden epiphany. Hell, who isn’t swept up in the lure of the road? And what writer (and Bern is nothing if not one) has not tackled its seduction from Homer to Joyce, Horace Greeley to Woody Guthrie, Kerouac to yours truly.

“I think subconsciously you choose what you choose to tell your stories about, but it’s not a conscious effort on my part,” Bern explained when a proper interview commenced in early June. “I’m not clever enough to make up something and realize its metaphoric significance, though I do think it’s a beautiful thing when the listener acts as my interpreter and takes the ride to that degree. That’s all I ever want from any song. It’s what any songwriter can ask — that the listener wrestles with it and lets the ideas reveal themselves. For me, it’s all the stuff of my mundane little life lifted by the power of song and maybe, subconsciously, you’ll tap into these things because similar experiences come up in all of our lives.”

Bern’s protestations to the contrary, these songs are not disparate ballads or ravers, wise-guy sing-a-longs or political harangues, the likes of which he has mastered over 16 years spanning 18 albums. “Maybe this is my swansong for that character,” Bern says. “But then again, maybe it never goes away.” Or as he sings in “Luke the Drifter” (the title a reference to country legend Hank Williams’ non-deplume), “Go or stay, one or the other.”

Drifter is a singular vision of a journey, the infinite search through snapshots and notations of every can-kicking crossroad conundrum. “Ooh, I do my share I knock about/Is anything gonna work out”? he sings in the hauntingly beautiful “The Golden Voice of Vin Scully,” as the interior echoes of the radio wave acts as a north star in a desert-scape Californian hymn worthy of Georgia O’Keefe’s pallet.

“Ultimately this stuff is therapy, isn’t it?” Bern muses. “Any literature is interpretation, the only difference being that most of the time you’re not talking to the writer.”

Drifter’s topographical references are vast. We visit the Milky Way, the moon, Madrid, Hollywood, New York City, Capetown, Johannesburg, North of Seattle to the Mexico line, San Bernardino, Haarlem, the black hills of Ohio/Wisconsin to the Indiana mud, the Canadian border, Philadelphia, West Virginia, and the solar system. Then there is time travel as in “Mexican Vacation,” where a train moves the narrator through the anarchic landscape of a pre-historic American construct overrun with slave-traders as he professes his love for the “runaway slave girl.”

A sense of travel even appears when we’re stuck in the obligatory isolation chamber of the traveling musician, the hotel room, which is wistfully depicted in “Party by Myself.” Bern’s bittersweet sampling of embraceable loneliness and mind-altering inertia is not unlike being suspended in outer space or in a capsule, which appears, as in the classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey to be still but is actually moving. Most interesting is Bern’s use of the two-dimensional image of Captain Kirk flickering on the tube, another iconic character set adrift “boldly going where no man has gone before.”

Kirk appears, as do all of Bern’s pop culture/historical figure references, brimming with symbolism, not the least of which is his nod to Jonathan Swift, who penned the immortal Gulliver’s Travels and for whom the poet W.P. Yeats once described in his epitaph as the “world-besotted traveler.”

“I suppose the interesting thing is that these songs were written at different times, instead of a concentrated period,” says Bern when pressed again about this coincidental subconscious spate of songs with the central theme of the passerby. “I started to write songs like ‘Raining in Madrid’ and ‘Haarlem’ in those places, while ‘Capetown’ is sort of a flight of the mind. And then, you know, LuLu came (his two-year old daughter), I moved out here (from New Mexico to Los Angeles) and, yeah, I think that kind of sparked the whole thing.”

I count Dan Bern as one of my closest colleagues and in many ways a brother in arms. We have tracked the bloody grounds of political and social battles and acted as sounding boards for each other’s work for close to a decade. Both of us have fathered daughters within a few years of each other and watched our generation begin to take charge of all that we railed against in our youth — the destruction of the earth, the systemic killing of innocents, the segmental repression of society, the global economic power-play — and we even managed to elect our own leader of the free world, and yet watch in horror as the madness continues unabated.

“Yeah, that’s true,” Bern chuckles, as he usually does when confronted by larger issues before whittling it down to his own corner of the world. “But also what’s true at the same time is we’re getting older and we have a feeling of our own mortality; we’re not young bucks anymore.” And then he makes sure I know that he doesn’t feel particularly in charge of anything.”I’m not even in charge of my house!” he laughs.

This may well be why Drifter is filled with the temporary escape provided by chemicals and booze, which pop up as playful landmarks along the way. Senses dulled just enough to continue the search for anything; — integrity, friendship, love, comfort? “Will I see you in the street tonight?” Bern sings in “Raining in Madrid,” as if drifting into random social interaction. But in “Home” his search flirts with futility, “Like a vagabond out on the lawn, I was almost gone,” but then suddenly he sings, “Find out who will stick it through thick and thin, lose or win, it’s how you get some place.”

The passion of the search has certainly inspired Bern’s singing. He has never sounded better or more controlled, completely at ease with these wonderfully crafted pieces, each one fastidiously pored over with absorbing precision. Here Common Rotation’s honeyed harmonies and weathered accompaniment on trumpet and banjo (Jordan Katz), harmonica and saxophone (Adam Busch) and guitar and dobro (Eric Kufs) lend the songs a weight they crave, a deserving ensemble for their poetic resonance.

“The truth is I worked on this record three-times longer than anything I’ve ever done,” Bern sighs when confronted with the events of the past three and a half years. “It becomes this thing that every little change that occurs in your sphere you apply it.”

The story of the making of Drifter could well have found its way into the work, as Bern and his ensemble, absent the umbrella of a record company this time around, sold songs, studio time, played private gigs and even composed personal jingles for outgoing phone messages for a host of donors all over the country, the time, expanse, and constant dissection of the project adding to its charm.

“The biggest thing is I didn’t have a wad of record company dough to go in and just do it,” Bern explains. “This record was done on everybody’s good graces and time. Money talks. It gets things done. It books studio time, it pays for musicians, it moves things along. And in a place like L.A. there’s all the people you want, but everybody’s doing a trillion things.”

Some of those people, like film songwriting partner, Mike Viola and a stirring guest appearance by the incomparable Emmy Lou Harris on the moving, “Swing Set,” serve the travel aesthetic well. We stop off into different voices and pass through musical styles, providing a station-to-station, truck stop ambiance of the rootless existence.

“There’s a line through this record, for sure,” admits Bern. “And that’s why I worked so hard to get to a sequence that works. It’s like you wouldn’t routinely skip over a scene in a movie to get to the next one. Even though there are fifteen songs here, they all play a role. Basically if something’s on there, it’s because it wouldn’t allow itself to be thrown off. It forced its way in and wouldn’t let go.”

Bern says the sequence of the songs became “like an accordion” for months upon months, jumping the total from 15 songs down to 12 and in some cases just eight and then back up again. “I finally went to Chuck Plotkin (famed producer of Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan, as well as Bern’s 2002 masterwork, New American Language) and sat with he and his wife for two full afternoons,” recounts Bern. “Turns out, I had the bulk of the run down, but he made a couple of important switches, which tied everything up. For me, if Chuck says it’s okay, then it’s okay.”

Once given the thumbs up from his musical sherpa, Bern quickly shifted gears and recorded 18 of his baseball songs with Common Rotation. Culled from nearly thirty years of work, which spans a century of the game’s most compelling characters and stories from The Babe to Barry Bonds, Doubleheader, aptly titled due to the 18 song list — a song an inning — was released on the heels of Drifter on July 4 when Bern played the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. “We just finished it six weeks ago,” he says excitedly, as if relieved to be free from the looming stranglehold of the Drifter marathon. “We just went in and did it all at once, boom; now all these songs I’ve been carrying around are under one roof.”

Beyond wrapping up Drifter and banging out Doubleheader, Bern hints that a third record of country songs, which he whispers may be the best of the three, is ready to go. “Probably for a good ten, fifteen years I was writing on average a song every ten days, like eighty songs a year, but now that seems paltry,” laughs Bern. “I pat myself on the back now if I can get through a tour without writing a song, allowing myself to stay present, because what writing does, as much as it’s this amazing thing that freezes moments, what you’re doing is freezing a rapidly approaching past moment. So while you’re scribbling and drawing your brain cells for a rhyme, maybe you miss that next passing cloud.”

And so here is Dan Bern, putting a ribbon on his troubadour life and turning his attention to the pastoral lore of the grand old game, which James Earl Jones so poignantly performed in Field of Dreams, a film more about the passage of time and the evolution of spirit than baseball. He could well have been reciting from Drifter: “The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game, is a part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that once was good, and it could be again.”

Or as Bern sings in the refrain of “Luke the Drifter,” “Life is tragic, somely/Life is magic, mostly.”

“I can’t tell you how much of my energy, attention, DNA is in Drifter,” concludes Bern. “But I am so personally relieved to not have to think about it anymore on a daily basis. It’s a happy, guilty, candy pleasure to talk about baseball. I guess it’s just easier to talk about baseball than myself.”

Drifting … drifting … drifting along.